* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Introduction - Australian Doctor

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

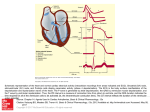

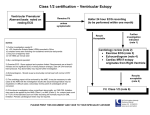

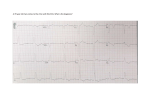

How to Treat PULL-OUT SECTION www.australiandoctor.com.au Complete How to Treat quizzes online www.australiandoctor.com.au/cpd to earn CPD or PDP points. INSIDE Bifascicular and trifascicular block First-degree atrioventricular block Left bundle branch block Early repolarisation pattern Wellens syndrome Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy the author Associate Professor Stefan Buchholz consultant cardiologist, Mackay Base Hospital, Cardiac Services Unit, Mackay; Associate Professor, James Cook University school of medicine, Mackay, Queensland. ECG conundrums Introduction THE 12-lead ECG is a diagnostic tool that is very valuable in the evaluation of cardiac complaints both for diagnostic and screening purposes, and to support referrals to specialist services. Most of the ECG findings that may trigger an immediate consequence — such as ST-segment deviation, complete heart block, supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome and ventricular fibrillation — have been covered in past How To Treat articles and will not be covered here. This article will concentrate on important ECG findings that are reasonably common in daily practice but not immediately associated with any obvious pathological abnormality or medical condition, including: • Chronic first-degree heart block. www.australiandoctor.com.au • Chronic bi- and trifascicular block. • Chronic left bundle branch block. • Early repolarisation pattern. • Wellens syndrome. • Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. cont’d next page Copyright © 2013 Australian Doctor All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission requests, email: howtotreat@cirrusmedia.com.au 22 November 2013 | Australian Doctor | 23 How To Treat – ECG conundrums Bifascicular and trifascicular block THERE has been considerable interest in the potential of various forms of cardiac conduction disturbances such as first degree atrio-ventricular as well as bifascicular or trifascicular block to degenerate into complete heart block. Bundle branch block is usually present when there is prolongation of the QRS duration. The conduction system distal to the AV node divides into left and right bundle branches. A block in one of the bundle branches from any cause will therefore lead to delayed activation of the corresponding ventricle. The term ‘trifascicular block’ is commonly applied in daily clinical practice, and it usually denotes the combination of right bundle branch block (RBBB), left anterior hemiblock/fascicular block (LAFB), and first-degree heart block. However, this term is inaccurately applied as it may confuse the issue in patients with RBBB and block in both fascicles of the left bundle branch, manifesting as complete heart block, or in patients with RBBB and left posterior hemiblock, as these entities could also be termed ‘trifascicular block’. Figure 1 demonstrates findings consistent with a bifascicular block. The underlying rhythm is sinus rhythm with a rate of about 55 beats per minute. The QRS is just over 120 milliseconds in duration, and there is rsR’ configuration in lead V1 and a broadened s-wave in leads I and V6, all consistent with RBBB. The main QRS vector axis should therefore be right-sided, with a maximum QRS height somewhere between +90º and +180º, with positive QRS complexes in leads aVF or III. As shown in the example, however, the main QRS vector is facing away from the right-sided (inferior) leads, with the maximum QRS Bifascicular block Figure 1: 12-lead ECG showing a ‘bifascicular block’ (right bundle branch block [RBBB] and left anterior hemi-block). being in aVL. This finding, together with predominant S-waves in leads II and III (that is, the ratio of R to S height is <1), is consistent with the main axis beyond -30º also termed left axis deviation. This is suggesting a concomitant left anterior fascicular block, the combination of which is then termed ‘bifascicular block’ (RBBB and LAFB). Progression to heart block One of the important clinical questions is: how often does asymptomatic chronic bifascicular or trifascicular block degenerate into symptomatic complete heart block, requiring some form of intervention or treatment? A large study from the early 1980s followed 554 patients with either bi- or trifascicular block. The study investigators were able to demonstrate that 1% of patients each year progressed to complete heart block.1 However, the majority of morbidity and mortality noted in this study was due to the development of tachyarrhythmia rather than bradycardia, or complete heart block. Quite a few studies from the mid-1970s, however, have shown a higher incidence of progression to complete heart block, ranging from 10-16% in patients with chronic RBBB and LAFB, to as high as 75% over a period of 1-6 years in patients with RBBB and left posterior fascicular block.2,3 Risk factors for deterioration Several risk factors have been found to be associated with progression to complete heart block, including syncope (with bifascicular block at time of presentation), chronic kidney disease, and a QRS duration of over 140 milliseconds. The presence of all of these three risk factors correlated with a 95% chance of developing complete heart block within one year of presentation, according to one study.4 Management Treatment options of chronic bi- or trifascicular block include cessation and avoidance of drugs that may slow conduction or prolong the refractory period of fascicular tissue and nodal conduction. Examples of medications to stop and avoid include beta-blockers, calcium antagonists (both dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine), digoxin and flecainide, among others (see Online resources). Other potentially reversible causes of impaired conduction, such as myocardial ischaemia (especially the right coronary artery that usually supplies the sinus node, AV-node and right fascicle) or electrolyte imbalance should be identified and corrected. Pacemakers If reversible causes have been corrected or excluded, then permanent pacemaker insertion in selected symptomatic patients is indicated. Some patients have an underlying neuromuscular disorder that predisposes them to cardiac disease and bundle branch block. These include myotonic dystrophy, Kearns–Sayre syndrome (a rare neuromuscular disorder characterised by retinitis pigmentosa, muscle weakness, ataxia, hearing loss and diabetes), and other forms of (usually inherited) muscular dystrophies. For these patients, a permanent pacemaker is more likely to be recommended. This is mainly because of the unpredictable nature of relentlessly advancing cardiac conduction disease inherent to these progressive muscular disorders. The choice of pacemaker (eg, single or dual chamber pacing, the rate–response system) is usually left to the discretion of the operator responsible for pacemaker insertion. In general, dual-chamber pacing is recommended as it maintains physiological sequential pacing of the atria and the ventricles. This helps to reduce the incidence of ‘pacemaker syndrome’, characterised by the uncomfortable awareness of palpitations due to atrial contraction against a closed mitral valve or, less likely, when atrial contraction occurs shortly after ventricular contraction with incomplete atrial filling (such as in marked first-degree heart block). First-degree atrioventricular block ATRIOVENTRICULAR (AV) conduction includes transmission of an electrical impulse from the atria to the ventricles, and ‘block’ is defined as a delay or interruption of this impulse, either temporary or permanent. Examples of AV block include first-degree block, seconddegree AV block such as Mobitz type I (Wenckebach periodicity) and Mobitz type II, and complete heart block. Only first-degree heart block is discussed in this section. Characteristics of PR interval AV impulse conduction deficit is defined as a delay of the PR interval beyond 200 milliseconds (one large square on the standard ECG). A normal PR interval is defined as ranging between 120 and 200 milliseconds. It tends to be shorter with faster heart rates, owing to generalised rate-related shortening of the action potential (which also accounts for the decreased QT interval seen with faster heart rates). Children tend to have a PR interval below 160 milliseconds. The PR interval is comprised of the following components of conduction: atrial depolarisation, AV nodal conduction, the His bundle 24 | Australian Doctor | 22 November 2013 and the infra-Hisian conduction system including the fascicles and Purkinje fibres (modified cardiac muscle fibres originating from the AV node). Pathophysiology of first-degree heart block It is generally accepted that the majority of cases of first-degree heart block are due to an intraatrial or AV nodal conduction defect. However, it must be pointed out that in rare instances the defect may be within the ventricular conduction system at, or well below, the His bundle, which makes no difference to the appearance of the PR interval on a standard 12-lead ECG. It has been estimated that intra-atrial block is responsible for about 3% of cases. Overall, about 80% are due to atrial or AV nodal delay.5,6 It is estimated that over 90% of patients with a PR interval over 300 milliseconds have AV nodal conduction block, as is frequently observed in patients with generalised increased vagal tone.7 Sympathetic and parasympathetic influences on the AV nodal conduction interval at rest are usu- ally tightly balanced. Enhanced vagal tone, such as during deep sleep, athletic training, intense pain, hypersensitive carotid sinus syndrome, and during episodes of vomiting or dry retching, are all known to increase the AV nodal conduction time to some degree (for an extreme example, please see case study at the end of the article). Clinical associations Asymptomatic first-degree AV block is common. It has been shown that, among 1000 healthy aircraft pilots, about 1.6% had PR intervals exceeding 280 milliseconds, without demonstrable cardiac structural abnormalities or symptoms.8 In some cases, however, AV nodal conduction block is associated with structural abnormalities of the heart. Examples include Ebstein’s anomaly (ventricularisation of the tricuspid valve), endocardial cushion defects (such as ostium primum atrial septal defect or cleft mitral valve as seen in Down syndrome), infiltrative cardiomyopathies (such as haemochromatosis or amyloidosis) and cardiomyopathies associated with www.australiandoctor.com.au neuromuscular disorders such as muscular dystrophy. Hence clinical assessment including transthoracic echocardiography can prove important in the evaluation of patients with otherwise asymptomatic first-degree AV block. There are some cases where first-degree AV block is associated with a widened QRS complex (over 120 milliseconds). This indicates pathology involving the infra-Hisian conduction system in about two-thirds of cases. His bundle ECGs as done during electrophysiological catheter studies provide the most accurate answer as to where the conduction slowing is occurring. Electrophysiology catheters have multiple sites to measure electrical impulses. During electrophysiology studies (EPS) it is usually possible to differentiate the length of the conduction system below, and including, the AV node, in much more detail then what is seen on a standard 12-lead ECG. Correlation with ECG Is it possible to clinically determine the site of the conduction block when reviewing a 12-lead ECG? On the whole, the ECG is of lim- ited value, however, a PR interval over 300 milliseconds with a normal QRS complex configuration and duration is most commonly due to AV nodal block (figure 2A), whereas widening of the QRS complex indicates a potential problem in the bundle branches. Pacemaker syndrome In some instances, the PR interval is markedly prolonged. In those cases, the P wave can morph into the preceding T wave which increased the amplitude of the T wave, as shown in figure 2B. This may cause clinical ‘pacemaker syndrome’, which consists of symptoms and signs related to AV-dyssynchrony (ie, atrial contraction against a closed mitral and tricuspid valve), such as dyspnoea, palpitations, malaise and syncope. Mimicking supraventricular tachycardia A markedly prolonged PR interval could also mimic supraventricular tachycardia, with complete loss of the P wave as shown in the example ECG. A way of differentiating PR prolongation in a patient with sinus tachycardia from a supraven- tricular tachycardia is shown in figure 2C. During the release phase of a Valsalva manoeuvre, for example, the sudden and brief appearance of P waves (arrows) can be appreciated. This appearance is due to the prolongation of the T-P interval (or R-R interval), which then separates the T wave from the P wave. A First-degree atrioventricular block Prognosis Several large-scale cohort studies have investigated the potential clinical impact of chronic firstdegree heart block. The prospective Framingham Heart Study found that healthy asymptomatic patients with a PR interval over 200 milliseconds are more likely to develop atrial fibrillation (140 vs 36 patients per 10,000 personyears), and need permanent pacemaker insertion (59 vs 6 patients for pacemaker implantation). They also had a 1.4 times higher adjusted risk all-cause mortality when compared to patients with normal AV conduction.9 This study included over 7500 patients who were followed over almost 40 years. A further prospective study of almost 1000 patients with stable coronary artery disease identified 87 patients with PR interval over 220 milliseconds. Compared with patients with normal AV conduction, these patients had a 2.3 times higher risk of hospitalisation for heart failure as well as cardiovascular mortality.10 Management Current evidence therefore suggests that first-degree AV block B C Figure 2: A: First-degree atrioventricular block. B: First-degree atrioventricular block in same patient during episode of tachycardia (anxiety related), showing fusion of the P and T wave with ‘disappearance’ of the P-wave. C: Dissociation of P and T wave during Valsalva manoeuvre (black arrows showing P-wave) in the same patient. Valsalva in healthy asymptomatic patients as well as in those with known coronary artery disease is associ- ated with a higher overall risk of cardiac morbidity and mortality. Most patients with first-degree AV block will not need permanent pacemaker insertion. This includes those who are asymptomatic or in whom AV block is expected to resolve and is unlikely to recur (such as in suspected medication toxicity, transient increase in vagal tone or decrease in oxygenation such as in obstructive sleep apnoea). The current North American guidelines (AHA/ACC 2008), however, conclude that permanent pacemaker insertion may be considered in patients with first-degree AV block associated with underlying neuromuscular disease (such as Erb’s dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy, or Kearns–Sayre syndrome), even when asymptomatic (class IIb recommendation; Level of Evidence: B). In terms of medical management, routine prophylactic anticoagulation is not advised, because the absolute number at risk is small in those without AF (see Framingham Heart Study mentioned earlier). Routine prophylactic anticoagulation would unnecessarily expose a lot of patients to antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. Once AF had established, anticoagulation would be recommended according to the usual guidelines. It is not necessary to follow patients without AF with repeated tests but it is important to make them aware of what palpitations feel like. There are no data on whether seemingly asymptomatic patients should be closely scrutinised for coronary artery disease. However, in patients with cardiovascular risk factors and firstdegree block, it is prudent to make a dedicated appointment and discuss primary prevention strategies with the patient. Left bundle branch block Clinical significance THE prevalence of left bundle branch block (LBBB) in young healthy males has been shown to be about 0.05%. Over 90% of these have no evidence of structural heart disease on further investigation.11 No increase in mortality was observed in the subpopulation without structural heart disease. Data from the Framingham Heart Study has shown that people who developed LBBB later in life (over 60 years of age) had a higher incidence of coronary heart disease and hypertension and that LBBB is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality. This finding has been confirmed by several other studies.12 Individuals with LBBB and type 2 diabetes usually have more severe and extensive coronary atherosclerosis when compared with patients with diabetes who do not have LBBB. Pathophysiology Most patients with LBBB have underlying coronary artery disease, not uncommonly involving the proximal part of the left anterior descending artery, which supplies all the proximal septal branches. The bundle of His divides into the right and left bundle branches just beyond the muscular and fibrous boundaries of the proximal septum. The left anterior descending artery supplies the left bundle branch, usually with some collat- Left bundle branch block Figure 3: Sinus rhythm with typical left bundle branch block. of the QRS complex (eg, positive QRS in V6 and negative ST and T in the same lead). ‘Negative’ QRS-T concordance, meaning negative ST or T waves in the anterior leads with negative QRS is unusual, and is usually associated with underlying ischaemia. Appropriate investigations The presence of LBBB makes diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia very difficult and a stress ECG is unlikely to be helpful due to the marked resting QRS abnormalities. Stress echocardiography or exercise nuclear perfusion imaging is therefore preferred when evaluating a patient for coronary artery disease. erals from the circumflex and right coronary artery. Other associations LBBB may also be associated with slowly advancing degenerative conduction system disease, infiltrative cardiomyopathies with normal coronary arteries, and completely healthy and structurally normal hearts. Interpreting the ECG The characteristic changes seen on a 12-lead ECG in LBBB are very dramatic. The diagnosis can usually be made through ‘pattern recognition’ rather than dissecting the ECG systematically. Loss of Q waves The main components usually found in ‘typical’ LBBB (figure 3) include a loss of the Q waves in the leftward leads — I, aVL, V5 and V6. Small Q waves in these leads are normal and reflect normal early proximal septal activation that usually causes Q wave deflections (<1mm in the anterior/chest leads and <2mm in the limb leads) when the cardiac muscle depolarises from the outside (epicardium) to the inside (endocardium) of the cardiac chambers. In LBBB, these Q waves are lost especially in lead I, but occasionally in lead aVL. Significance of large Q waves A potential clue for the presence of www.australiandoctor.com.au Management underlying coronary artery disease is a significant Q wave that is larger and broader than expected in LBBB in these leads. Figure 3 is an ECG taken from a patient four months after anterior STEMI. The black arrow shows a significant Q wave in lead aVL, larger and broader than expected in LBBB, and hence raises suspicion of coronary artery disease. QRS complex changes The QRS complex in LBBB is large and dysmorphic, the duration usually prolonged at over 120 milliseconds, with broad or notched R waves in the leftward leads, and occasional RS pattern in V5 and V6. The ST and T waves are most commonly divergent to the direction Given the association of cardiovascular disease with LBBB, these patients should be carefully evaluated for arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, and other disorders associated with conduction disease, such as myocarditis, infiltrative cardiomyopathies, valvular heart disease and, rarely, hyperkalaemia. For patients with an isolated LBBB and no evidence of underlying structural heart or coronary disease, no specific therapy is required. Patients with LBBB and unexplained syncope may be considered for permanent pacemaker insertion, especially when further conduction abnormalities such as second or third degree are subsequently documented. cont’d next page 22 November 2013 | Australian Doctor | 25 How To Treat – ECG conundrums Early repolarisation pattern THE early repolarisation pattern is not uncommonly seen on ECGs of younger individuals, with an estimated prevalence of about 10%. It has long been thought to represent a ‘benign’ variant of a normal ST segment. Recent studies suggest, however, early repolarisation pattern is not ‘benign’ a priori, just as ‘benign’ intracranial hypertension is not necessarily ‘benign’. Figure 4: 12-lead ECG of a young asymptomatic male with a J-point elevation of at least 0.2 mV (two small squares) in the inferior (II, III, aVF) as well as the lateral leads (V5 and V6). Early repolarisation pattern J-point is elevated in early repolarisation In early repolarisation, the ECG changes include elevation of the J-point (defined as the junction between the end of the QRS complex and the beginning of the ST segment, normally level with or <0.1mV above the PR segment on the ECG) by more than 0.1mV in at least two contiguous leads. Figure 4 shows a 12-lead ECG of a young asymptomatic male with a J-point elevation of at least 0.2 mV (two small squares) in the inferior (II, III, aVF) as well as the lateral leads (V5 and V6). The insert A shows the exact location of the J-point and its elevation, a feature absent from the ECG insert B without J-point elevation. Most commonly, in early repolarisation the J-point is elevated in either all of the inferior leads, or all of the anterior chest leads. Occasionally the J-point elevation would be found in both the inferior leads and the anterior chest leads. Differential diagnoses Differential diagnoses of J-point elevation include J-waves (also known as Osborn waves), which are transiently seen in cases of hypothermia, acute myo-pericarditis and ST-segment elevation myocardial injury. Marked J-waves or J-point elevation are also seen in Brugada syndrome, although the J-point elevations are usually only seen in the right precordial leads V1-V3. Progress and clinical associations It has been demonstrated that early repolarisation pattern may be a transient phenomenon. In a study involving over 500 individuals with early repolarisation pattern on baseline ECG, about 20% of the subjects did not have the pattern at the fiveyear follow-up study.13 Inheritance patterns Some studies have shown a twoto threefold increase in the probability that a first-degree relative of a person with early repolarisation pattern will also have the same ECG pattern. This raises the question of whether early repolarisation pattern could be inherited. Rarely, families with early repolarisation pattern and a high incidence of sudden cardiac death have been identified. An autosomal dominant inheritance in such families was suggested. If such an association exists, early repolarisation pattern could represent a potential health hazard rather than being benign as previously thought. Predisposition to ventricular fibrillation A large case–control study has shown the prevalence of early repolarisation pattern is 31% in more than 200 patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation compared with only 5% in over 400 healthy control individuals. Over a six-year follow-up there was a 2.1 times higher rate of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks for recurrent VF in patients with early repolarisation pattern than in the healthy control population.14 It appears that the greatest risk of VF is associated with early repolarisation in the inferior leads > 0.2mV. However, early repolarisation pattern is reasonably common in young asymptomatic individuals, and unexplained or idiopathic VF is very rare. Larger studies have estimated the incidence of idiopathic VF in a person younger than 45 years to be 3 in 100,000. The incidence increases to 11 in 100,000 when early repolarisation pattern is present.15 This finding has been confirmed by a recent meta-analysis involving more than 140,000 early repolarisation pattern-positive individuals with a collective 3.6 million personyears follow-up. The study demonstrated a 1.7 times increased risk of arrhythmic death compared with an equally large control group. The estimated absolute risk difference of early repolarisation patternpositive subjects was 70 cases of death attributed to primary cardiac arrhythmia per 100,000 personyears. Again, early repolarisation pattern in the inferior leads was identified as the ECG location conferring the highest risk. The exact mechanism that causes the early repolarisation pattern is not well understood, and the precise mechanism for VF is unknown. In all likelihood early repolarisation and VF are due to ion-channel current imbalance, possibly similar to Brugada syndrome or short QT syndrome. Further research is underway to elucidate the potential genetic basis for this disorder. Treatment Because of the high prevalence of early repolarisation pattern in the general population, the current consensus is that no additional tests or investigations are indicated, unless there is a history of syncope or familial sudden cardiac death. Such patients should be further evaluated, ideally in a specialist cardiology clinic. Survivors of sudden cardiac arrest due to otherwise unexplained primary VF arrest, are best treated with an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator. Class 1a antiarrhythmic therapy may be indicated as a therapeutic option in an early repolarisation pattern-positive patient with recurrent VF after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. However, the choice of antiarrhythmic therapy needs to be individualised. Emergency treatment In patients with known or suspected early repolarisation pattern presenting with sudden cardiac arrest and ongoing episodes of recurrent VF, intravenous isoproterenol has been shown to be beneficial in suppressing VF storm. Wellens syndrome WELLENS syndrome is named after Dutch cardiologist Hein Wellens. It is a potentially very dangerous cardiac condition that may go unnoticed because of the timing of ECG changes and the occasional non-specific appearance. Wellens syndrome has been convincingly linked to an imminent occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, threatening infarction of the anterior left ventricle, usually involving a large area. Figure 5: Sinus rhythm ECG from a patient with a subacute proximal left anterior descending artery occlusion. A: The more common ‘type 1’ Wellens ECG. B: The uncommon ‘type 2’ Wellens ECG. Wellens syndrome Management Diagnosis The syndrome criteria include characteristic ‘Wellens-type’ anterior T-wave changes, recent history of chest pain suggestive of angina, little or no cardiac biomarker elevation, normal precordial R-wave progression without Q waves (this excludes previous anterior infarction which can mimic the ECG changes in Wellens syndrome), and no significant ST elevation. ECG findings The ECG changes associated with this syndrome can be very subtle, and are usually confined to the anterior precordial leads, most 26 | Australian Doctor | 22 November 2013 may therefore be entirely missed if serial ECGs are not being done. In Wellens’ original description, only about 1 in 10 patients had cardiac biomarker elevation; the ECG may be the only indication of an impending infarct in an otherwise pain-free patient. Therefore, a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained when dealing with patients who may have Wellens syndrome. commonly seen in V2-V4. Two different ECG pattern have been described by Wellens’ team: the more common ‘type 1’ (figure 5A), with deep symmetrical T-wave inversion, and ‘type 2’ (figure 5B), causing rather subtle biphasic T waves anteriorly. Type 2 Wellens ECG is less common (only about 25% of patient with the syndrome display this ECG pattern), and may go either completely unnoticed by automated computerised ECG interpretation algorithms or is being reported as ‘non-specific’. Both ECG types are consistent www.australiandoctor.com.au with a pre-infarction stage (when seen in the setting of symptoms and signs suggesting an acute coronary syndrome), and impending occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. These ECG changes interestingly do not appear until about 4-6 hours after the onset of angina, and Exercise stress testing is contraindicated in Wellens syndrome as this could lead to acute infarction and VF arrest. Urgent admission to a coronary care unit and expedited inpatient transfer to a percutaneous coronary intervention-capable hospital for coronary angiography is recommended if these ECG changes occur in the context of symptoms and signs suggesting an acute coronary syndrome. Additionally, these patients should be medically treated as per current guidelines for an acute coronary syndrome/ NSTEMI. cont’d page 28 How To Treat – ECG conundrums Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy THE prevalence of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is estimated at about 1 in 3000. This condition is an important cause of sudden cardiac death in young adults. It is probably underrecognised as some of the clinical symptoms and signs can be very subtle. References Figure 6: Transthoracic echocardiogram from the subcostal view, showing a dilated, infiltrated and thickened right ventricle (white arrows). Increased rate of sudden cardiac death It is estimated that 10% of cases with sudden cardiac death are due to ARVC. The condition is characterised by right ventricular scarring with patchy fibrous or fibro-fatty replacement of the normal myocardium, ultimately leading to right ventricular dilatation (figure 6). The mean age at diagnosis is about 30 years. It has been suggested that about 30% of cases are familial, involving the desmoplakin– desmosomal protein discs that connect myocytes electrically. A European study has found that the incidence of ARVC in sudden cardiac death in athletes may be as high as 20%.16 This may be at least partly due to abnormal stress response of the right ventricle and impaired sensitivity to catecholamines resulting in abnormal cardiac sympathetic function. A RVOT ventricular tachycardia @ 220 bpm, LBBB Diagnosis The diagnostic criteria for ARVC are complex and based on findings obtained by 2D echocardiography, 12-lead ECG, cardiac MRI, endomyocardial biopsy and family history.17 B RVOT ventricular tachycardia @ 260 bpm, with RBBB Genetic inheritance patterns Autosomal dominant transmission is most common, however larger families with autosomal recessive inheritance have been identified. This is especially the case in the Mediterranean area where ARVC is part of the ‘Naxos’ syndrome (named after a Greek island with a very high prevalence of autosomal recessive ARVC). This cardiocutaneous syndrome also presents with palmoplantar keratoderma and frizzy hair. Figure 7: A: Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) ventricular tachycardia from a patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. B: ‘Common’ ventricular tachycardia originating within the left ventricle, hence showing RBBB activation. Clinical presentation About 40% of cases with ARVC are asymptomatic. They are usually picked up during family screening of an identified patient. As many as 50% of patients have a normal ECG at presentation, especially those with no significant or minimal right ventricular thickening, dysplasia or dilatation. When symptomatic, the principal features include palpitations (not uncommonly triggered by stress or physical exertion), syncope and, as mentioned, sudden cardiac death. Although ventricular tachycardia is the most common arrhythmia, patients with ARVC can present with supraventricular tachycardia (atrial tachycardia, AF or flutter). Ventricular tachycardia Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is identified as a monomorphic nonsustained or sustained broad complex tachycardia with a LBBB morphology (this is because the VT frequently originates in the right ventricular free wall and then traverses across the septum to the left ventricle). Figure 7 shows two different VTs: figure 7A has been taken from a 39-year-old male with exercise-induced VT, with underlying ARVC. Note the VT main vector and precordial QRS configuration in this case is consistent with LBBB, 28 | Australian Doctor | 22 November 2013 tricular ARVC or, rarely, left ventricular involvement only. A B C D ECG findings Although as many as 50% of patients have a normal ECG at presentation, the following changes may be the first clue to the presence of underlying ARVC: • Epsilon wave (figure 8A): An epsilon wave, present in up to 30% of cases, represents multiple low amplitude after-depolarisations caused by delayed activation of the right ventricle. This ECG finding is very suggestive of ARVC and is usually present in advanced stages of right ventricular involvement. The epsilon wave, especially when prominent, can be mistaken for a P wave. • T-inversion in the right precordial leads (usually V1-V3, figure 8B): This is not a sensitive (only positive in 50% at presentation) nor specific (also seen in Brugada syndrome) ECG finding, and is said to correlate with right ventricular dilatation. • Right ventricular conduction delay, incomplete RBBB, or QRS prolongation over 110 milliseconds in the absence of a ‘typical’ RBBB (figure 8C), are uncommon overall but highly specific findings. • Delayed upstroke of the S wave in any of the right precordial leads (V1-V3), defined as the interval from the nadir of the S wave to the end of the QRS over 55 milliseconds (about 1.5 small squares on the standard ECG with 25mm per second paper speed, figure 8D). In the example given, the delay in S wave upstroke is 2 small squares = 80 milliseconds). Management Figure 8: 12-lead ECG taken from a patient who had a history of symptomatic VT and underlying ARVC. A: Epsilon wave. B: T-inversion in a right precordial lead. C: Prolongation of the QRS complex due to after-depolarisations (epsilon-wave). D: Delayed S-wave upstroke. with negative QRS in lead V1. Insert B demonstrates a VT originating in the left ventricle (hence with RBBB and positive QRS deflection in V1) in a patient with ischaemic heart disease. Determining whether LBBB or RBBB is present, to some degree, may help to at least narrow down whether the VT originates in the left or the right ventricle. That said, there are quite a few case reports in the literature demonstrating bivenwww.australiandoctor.com.au Current guidelines suggest that cardioverter-defibrillator implantation should be reserved for select patients. These include those with sustained VT, cases of survived sudden cardiac arrest, primary VF or for selected high-risk patients (eg, patients with extensive disease with right ventricular and left ventricular involvement, one or more affected family members with sudden cardiac death, or undiagnosed syncope, among others). Individuals with ARVC, even when asymptomatic, should not partake in intense endurance training or competitive sports. 1. McAnulty JH, et al. Natural history of ‘high-risk’ bundle-branch block: final report of a prospective study. New England Journal of Medicine 1982; 307:137-43. 2. K ulbertus HE. The magnitude of risk in developing complete heart block in patients with LAD-RBBB. American Heart Journal 1973; 86:278-80. 3. S canlon PJ, et al. Right bundlebranch branch block associated with left superior or inferior intraventricular block. Clinical setting, prognosis, and relation to complete heart block. Circulation 1970; 42:1123-33. 4. M arti-Almor J, et al. Novel predictors of progression of atrioventricular block in patients with chronic bifascicular block. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia 2010; 63:400-08. 5. N arula OS. Atrioventricular block. In: Cardiac Arrhythmias: Electrophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1979. 6. P euch P. The value of intracardiac recordings. In: Krikler D, Goodwin JF (editors). Cardiac Arrhythmias. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1975. 7. J osephson ME. Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology: Techniques and Interpretations, 2nd edn. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, 1993. 8. G raybiel A, et al. Analysis of the electrocardiogram obtained from 1000 young healthy aviators; ten year follow-up. Circulation 1954; 10:384-400. 9. C heng S, et al. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. Journal of the American Medical Association 2009; 301:2571-77. 10. C risel RK, et al. First-degree atrioventricular block is associated with heart failure and death in persons with stable coronary artery disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. European Heart Journal 2011; 32:1875-80. 11. R otman M, Triebwasser JH. A clinical and follow-up study of right and left bundle branch block. Circulation 1975; 51:477-84. 12. S chneider JF, et al. Newly acquired left bundle branch block: the Framingham study. Annals of Internal Medicine 1979; 90:303-10. 13. T ikkanen JT, et al. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. New England Journal of Medicine 2009; 361:2529-37. 14. H aissaguerre M, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. New England Journal of Medicine 2008; 358:201623. 15. R osso R, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: incidence and clinical significance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2008; 52:1231-38. 16. C orrado D, et al. Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in young athletes. New England Journal of Medicine 1998; 339:364-69. 17. M arcus FI, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010; 121:1533-41. Online resources Overview of Arrhythmias (includes medications that may cause impaired conduction): bit.ly/19NTiA cont’d page 30 How To Treat – ECG conundrums Case study Conclusion A PREVIOUSLY healthy 32-yearold woman was admitted to the ICU after a series of blackouts during a hens’ night party. It transpired that she passed out three times in quick succession without premonitory symptoms or signs. All three blackouts happened straight after she bent forward to vomit. Usually not keen on drinking alcohol, she admitted that she had drunk “way too much” during the party. She remembered that she passed out twice for a few seconds onto the bathroom floor right after a large vomit, and another time while she was lying flat on a bed, heaving and dry retching. Her past medical history was unremarkable and she was not on any prescription medication. However, she mentioned that she had experienced syncope seven years ago when she had vomited during an episode of food poison- Figure 9: Patient’s ECG, showing a six-second pause due to asystole. ing. At the time, the syncope was felt to be due to dehydration. Initial examination revealed an inebriated slim female without apparent distress. She was haemodynamically stable, blood pressure recorded via a left radial arterial line was 140/60mmHg, and heart rate of 60 beats per minute. Initial blood work was unremarkable, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and BSL were normal, and 12-lead ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. During an episode of dry retching, however, she suddenly became unresponsive, with an ECG showing a six-second pause due to asystole (figure 9). A second episode of retching resulted in a 20-second asystole, necessitating CPR and emergency insertion of a temporary pacing wire. Complete this quiz online and fill in the GP evaluation form to earn 2 CPD or PDP points. We no longer accept quizzes by post or fax. The mark required to obtain points is 80%. Please note that some questions have more than one correct answer. ECG conundrums — 22 November 2013 2. W hich TWO statements are correct regarding bifascicular and trifascicular blocks? a) R isk factors associated with the progression of a partial bundle branch block to complete heart block, including syncope, chronic kidney disease and a QRS duration of >140ms b) T here is an annual 40% risk of progressing to complete heart block c) U p to 75% of patients with a right bundle branch block and left posterior fascicular block will progress to complete heart block over a period of 1-6 years d) A ll bifascicular or trifascicular blocks should be treated with permanent pacemaker unless contraindicated 3. W hich TWO statements are correct regarding first-degree heart block? a) O nly 3% of first-degree heart blocks are due to intra-atrial block b) P atients with haemochromatosis may have associated first-degree heart block THE 12-lead ECG is an invaluable diagnostic tool in the evaluation of cardiac complaints. There are many significant ECG changes that are commonly found in daily medical practice but may not trigger an immediate consequence. Chronic first-degree heart block and other bundle branch block patterns are often diagnosed on asymptomatic patients. While there is no immediate lifethreatening consequence of these ECG patterns, long-term followup and management is important to prevent complications. Conditions such as Wellens syndrome and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy are uncommon and the ECG changes may be subtle but have significant prognostic implications. A correct diagnosis may be instrumental in saving the life of the patient. Instructions How to Treat Quiz 1. W hich TWO statements are correct regarding the electrical tracings of the heart? a) T he PR interval reflects atrial depolarisation, AV nodal conduction, His bundle and the infra-Hisian conduction system b) T he PR intervals in children are longer than in adults c) T he J-point is defined as the point of peak amplitude of the T wave d) S mall Q waves are physiological deflections of the electrocardiac conduction when the cardiac muscle depolarises from the epicardium to the endocardium The underlying diagnosis was consistent with neurally mediated reflex syncope, which can be classified according to the pattern of change in heart rate or BP into vasodepressor (vasodilatory hypotension), cardioinhibitory (bradycardia/asystole), or a mixture of the two main patterns. Markedly increased parasympathetic–vagal activity (dry retching and vomiting), in susceptible individuals, may acutely shorten the atrial refractory period (potentially causing atrioventricular blockade) and/or inhibit impulse generation in the sinoatrial node, causing sinus arrest/asystole. In the case presented, the cardio inhibitory component was felt to be playing the dominant role, and therefore dual-chamber permanent pacing was recommended and carried out, with the patient remaining well during 12 months’ follow-up. GO ONLINE TO COMPLETE THE QUIZ www.australiandoctor.com.au/education/how-to-treat c) First-degree heart block is characterised by a normal QRS complex d) A PR interval >300ms with a normal QRS indicates a potential problem in the bundle branches 4. Which TWO statements are correct regarding left bundle branch blocks? a) New-onset left bundle branch block after the age of 60 is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease b) A negative QRS-T concordance in the anterior leads excludes underlying cardiac ischaemia c) An exercise stress test should be the firstline investigation for left bundle branch block with suspected myocardial ischaemia d) Left bundle branch block and type II diabetes together increase the risk of more severe and extensive coronary atherosclerosis 5. Which TWO statements are correct regarding early repolarisation patterns? a) Familial early repolarisation pattern in an autosomal dominant inheritance is benign b) Early repolarisation pattern has a sixfoldhigher association in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation than those without c) All early repolarisation patterns should be thoroughly investigated to prevent complications d) Twenty per cent of patients with early repolarisation pattern do not exhibit this pattern five years later 6. Which TWO statements are correct regarding Wellens syndrome? a) Wellens syndrome is characterised by ischaemic chest pain, raised cardiac enzymes and pathological anterior Q waves b) The ECG changes associated with Wellens syndrome are typically confined to the anterior precordial leads, most commonly seen in V2-V4 c) Any patient suspected of having Wellens syndrome should undertake an exercise stress test immediately d) Serial ECGs should be taken at 4-6 hours after the onset of ischaemic chest pain in suspected Wellens syndrome 7. Which TWO statements are correct regarding arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy? a) The mean age at diagnosis is about 30 years b) This condition is typically due to spontaneous mutation c) More than 90% of cases with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy are silent, with a normal ECG d) Epsilon waves are very suggestive of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and are found in up to 30% of cases 8. Katie is a 47-year-old woman who presented for follow-up on a past history of first-degree heart block found incidentally. Which TWO statements are correct? a) Asymptomatic first-degree heart block is rare b) Efforts should be made to exclude underlying medication toxicity and obstructive sleep apnoea c) Echocardiography is never indicated when an ECG had been done to confirm the history d) A markedly prolonged PR interval in firstdegree heart block could look just like supraventricular tachycardia 9. Katie is otherwise healthy. Which TWO statements are correct regarding her prognosis? a) Katie has a 1.4-times-higher risk for all-cause mortality compared with a person with normal AV conduction b) Since she is asymptomatic, Katie can expect to have no higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation than any other patient with normal AV conduction c) Even if Katie develops underlying coronary artery disease, she will have no higher risk of cardiovascular mortality compared with patients with normal AV conduction d) If her PR interval elongates, Katie may be at risk of developing AV dyssynchrony 10. A repeat ECG showed that Katie has developed trifascicular block. Which TWO statements are correct regarding this development? a) A trifascicular block is another name for a complete heart block b) The majority of morbidity and mortality from trifascicular block is due to the development of tachyarrhythmia c) Dihydropyridine calcium antagonists should be avoided while non-dihydropyridine antagonists may be used d) Katie should be referred for investigation to identify and correct any underlying coronary ischaemia CPD QUIZ UPDATE The RACGP requires that a brief GP evaluation form be completed with every quiz to obtain category 2 CPD or PDP points for the 2011-13 triennium. You can complete this online along with the quiz at www.australiandoctor.com.au. Because this is a requirement, we are no longer able to accept the quiz by post or fax. However, we have included the quiz questions here for those who like to prepare the answers before completing the quiz online. how to treat Editor: Dr Steve Liang Email: steve.liang@cirrusmedia.com.au Next week General practice provides many opportunities for research, but GPs are often reticent about participating. Our special How to Treat next week is a comprehensive guide to research projects in general practice. The authors are Associate Professor Amanda McBride, head of general practice and discipline leader — general practice, school of medicine, University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney, and Dr Charlotte Hespe, head of general practice and head of general practice research, school of medicine, University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney, NSW. 30 | Australian Doctor | 22 November 2013 www.australiandoctor.com.au