* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Exterior Angle Inequality, AAS

Multilateration wikipedia , lookup

Noether's theorem wikipedia , lookup

Riemann–Roch theorem wikipedia , lookup

Reuleaux triangle wikipedia , lookup

Perceived visual angle wikipedia , lookup

Brouwer fixed-point theorem wikipedia , lookup

Four color theorem wikipedia , lookup

Rational trigonometry wikipedia , lookup

History of trigonometry wikipedia , lookup

Trigonometric functions wikipedia , lookup

Euler angles wikipedia , lookup

Integer triangle wikipedia , lookup

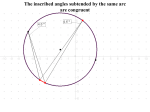

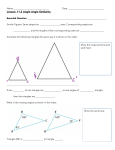

Exterior Angle Inequality Definition: Given ÎABC, the angles pACB, pCBA, and pBAC are called interior angles of the triangle. Any angle that forms a linear pair with an interior angle is called an exterior angle. In the the diagram below, point D is such that A*C*D, and pBCD is an exterior angle. Corresponding to this exterior angle are the remote (or opposite ) interior angles pABC and pCAB. Theorem (The Exterior Angle Inequality): In any triangle, an exterior angle has greater measure than either of the remote interior angles. That is, given ÎABC and point D such that A*C*D, . ~ Given ÎABC and point D such that A*C*D: Find the midpoint M of and find point E such that A*M*E and AM = ME. Construct segment . By the X Theorem, E and B are on the same side of , and since both A*C*D and A*M*E, E and D are on the same . Thus, point E is interior to pBCD, and we have . Also, since BM = CM, AM = EM, and the vertical angles pBMA and pCME are congruent, SAS gives us ÎBMA ÎCME. CPCF gives us µ(pMBA) = µ(pMCE). Thus µ(pBCD) = µ(pBCE) + µ(pECD) > µ(pBCE) = µ(pABC). side of Now to show that µ(pBCD) > µ(pCAB), we utilize the work we just did. Find point F such that B*C*F. Note that pBCD and pACF are vertical angles and are therefore congruent; µ(pBCD) = µ(pACF). But then, the exact construction we have just done can be used to show µ(pACF) > µ(pCAB). Find the midpoint N of , and G with B*N*G and BN = NG. We can show G is interior to pACF, use SAS to get ÎBAN ÎGCN and CPCF to get µ(pNCG) = µ(pNAB), and so µ(pBCD) = µ(pACF) = µ(pACG) + µ(pGCF) > µ(pACG) = µ(pCAB). A couple of corollaries not in out text: Corollary 1: The sum of the measures of any two angles of a triangle is less than 180. ~ Given two angles we will call angles p1 and p2. Form the exterior angle supplementary to p2; then 180 = µ(p2) + µ(p3) > µ(p2) + µ(p1). Corollary 2: A triangle can have at most one right or obtuse angle. (An immediate consequence of Corollary 1). Corollary 3: Base angles of an isosceles triangle are acute. (An immediate consequence of Corollary 2) Corollary (Uniqueness of Perpendiculars): For every line l and for every point P external to l, there exists exactly one line m such that P is on m and l z m. ~ We proved in the last section that such a perpendicular line exists; it remains to show that it is unique. We call that line m and the point where l and m intersect point Q. Now suppose for contradiction that there is another line n with P on n and n z l. Let R be the point of intersection of l and n. Now pPQR and pPRQ are right angles, as is pPRS. But pPRS is an exterior angle for the triangle, and must be strictly larger than pPQR, which it is not. This contradiction establishes the theorem. Note: For a different contradiction, we could have noted that, contrary to Corollary 2 above, has two right angles. Theorem (AAS Congruence): If under some correspondence, two angles and a side opposite one of the angles of one triangle are congruent, respectively, to the corresponding two angles and side of a second triangle, then the triangles are congruent. ~ (Outline of proof; you fill in the details as part of homework problem 6.6.) Given the correspondence with pA pX, pBpY, and . Our strategy is to show pCpZ and apply ASA. So, WLOG, we assume for contradiction that µ(pC) > µ(pZ). Construct ray such that µ(pACP) = µ(pZ) and between and . (How?) Now P is interior to pACB and so meets at some point D. (Why?) Now ªADC ªXYZ by ASA, and so µ(pADC) = µ(pY), by CPCF. But: µ(pADC) > µ(pB) = µ(pY), contradicting the exterior angle inequality. So pCpZ, and ASA completes the proof. -ish. The book chooses this point to discuss the Hypotenuse-Leg (HL) Theorem, but I prefer to do it later. The last theorem of this section is the SSS theorem, which the book proves by leaving it to you as an exercise. It can be proved as a consequence of the triangle inequalities in the next section. Here, I’ll prove it using the method suggested in the textbook, which is made simpler by a simple lemma we talked about in class. Lemma: The set of all points equidistant from each of two points A and B is the perpendicular bisector of . ~ This proof is a straightforward application of isosceles triangles and congruence theorems, and makes a good exercise. Be sure to prove both that if a point P is equidistant from A and B it is on the perpendicular, and that if P is a point on the perpendicular bisector it is equidistant from A and B. -ish. Theorem (SSS Congruence): If under some correspondence, three sides of one triangle are congruent to the corresponding three sides of another triangle, then the two triangles are congruent under that correspondence. ~ Let the two triangles be ÎABC and ÎXYZ under the correspondence ABC : XYZ. Using the Protractor and Ruler Postulates, find a ray on the side of opposite from B, and such that µ(pCAP) = µ(pZXY), and find a point D on such that AD = XY. Note that since AC = XZ, AD = XY, and µ(pCAD) = µ(pZXY), ÎADC ÎXYZ by SAS. Now, since AD = XY = AB, A is equidistant from B and D. Also, since BC = YZ = DC, C is also equidistant from B and D. Thus both A and C are on the perpendicular bisector of perpendicular bisector of , so is the . In ÎABD, since AE = AE, µ(pAEB) = 90 = µ(pAED), and BE = DE, SAS gives us ÎABE ÎADE and CPCF gives us pBAE pDAE. This congruence, along with AB = AD and AC = AC, allows us to use SAS to get ÎABC ÎADC, and since ÎADC ÎXYZ we have ÎABC ÎXYZ. Note: The argument above depends on A*E*C (where did we use that fact without mentioning it?). However, it could be that A*C*E or E*A*C. It also could be that A = E or C = E. As an exercise, complete the proof for these cases, one of which is illustrated below. This proof of SSS uses what are called “kites” and “darts” which are the shapes of the objects constructed by putting the two triangles together. The proof using triangle inequalities is actually shorter.