Prove if n 3 is even then n is even. Proof

... rational number. Assume that their sum is rational, i.e., q+r=s where s is a rational number. Then q = s-r. But by our previous proof the sum of two rational numbers must be rational, so we have an irrational number on the left equal to a rational number on the right. This is a contradiction. Theref ...

... rational number. Assume that their sum is rational, i.e., q+r=s where s is a rational number. Then q = s-r. But by our previous proof the sum of two rational numbers must be rational, so we have an irrational number on the left equal to a rational number on the right. This is a contradiction. Theref ...

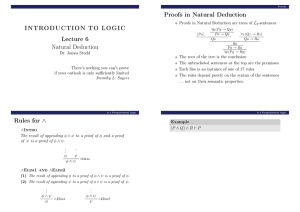

INTRODUCTION TO LOGIC Lecture 6 Natural Deduction Proofs in

... Informal reasoning with arbitrary names (C) Every person is either a quorn-lover or a person Informal proof. Let an arbitrary thing be given. Call it ‘Jane Doe’. Clearly, if Jane Doe is a person, then Jane Doe is either a quorn-lover or a person. So: every person is either a quorn-lover or a person. ...

... Informal reasoning with arbitrary names (C) Every person is either a quorn-lover or a person Informal proof. Let an arbitrary thing be given. Call it ‘Jane Doe’. Clearly, if Jane Doe is a person, then Jane Doe is either a quorn-lover or a person. So: every person is either a quorn-lover or a person. ...

Math 319/320 Homework 1

... Problem 1. Write (in words) the negation of each of the following statements: (i) Jack and Jill are good drivers. (ii) All roses are red. (iii) Some real numbers do not have a square root. (iv) If you are rich and famous, you are happy. Problem 2. Provide a counterexample for each of the following s ...

... Problem 1. Write (in words) the negation of each of the following statements: (i) Jack and Jill are good drivers. (ii) All roses are red. (iii) Some real numbers do not have a square root. (iv) If you are rich and famous, you are happy. Problem 2. Provide a counterexample for each of the following s ...

Writing Mathematical Proofs

... then use this assumption with definitions and previously proven results to show that the conclusion must be true. Direct Proof Walkthrough: Prove that if a is even, so is a2. Universally quantified implication: For all integers a, if a is even, then a2 is even. Claim: If a is even, so is a2. Pf: Let ...

... then use this assumption with definitions and previously proven results to show that the conclusion must be true. Direct Proof Walkthrough: Prove that if a is even, so is a2. Universally quantified implication: For all integers a, if a is even, then a2 is even. Claim: If a is even, so is a2. Pf: Let ...

Upper-Bounding Proof Length with the Busy

... on the length used to encode the statement. This bound uses the Busy Beaver function, as shown in the next section, in which we reproduce Chaitin’s argument. This paper presents an analogous result about proofs. It is likewise commonly held that no matter how hard you’ve tried and failed to prove a ...

... on the length used to encode the statement. This bound uses the Busy Beaver function, as shown in the next section, in which we reproduce Chaitin’s argument. This paper presents an analogous result about proofs. It is likewise commonly held that no matter how hard you’ve tried and failed to prove a ...

p | q

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

x| • |y

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

Give reasons for all steps in a proof

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

... when Q says a contradiction something is not true. Proof by Cases Break the domain into Try this for proving two or more subsets properties of numbers and prove PQ for the where odd and even elements in each such or positive and negative numbers subset. require different proofs. Counterexample Prov ...

Lecture notes #2 - inst.eecs.berkeley.edu

... and the other column lists the justifications for each statement. The justifications invoke certain very simple rules of inference which we trust (such as if P is true and Q is true, then P ∧ Q is true). Every proof has these elements, though it does not have to be written in a tabular format. And m ...

... and the other column lists the justifications for each statement. The justifications invoke certain very simple rules of inference which we trust (such as if P is true and Q is true, then P ∧ Q is true). Every proof has these elements, though it does not have to be written in a tabular format. And m ...

Lecture notes #2: Proofs - EECS: www

... and the other column lists the justifications for each statement. The justifications invoke certain very simple rules of inference which we trust (such as if P is true and Q is true, then P ∧ Q is true). Every proof has these elements, though it does not have to be written in a tabular format. And m ...

... and the other column lists the justifications for each statement. The justifications invoke certain very simple rules of inference which we trust (such as if P is true and Q is true, then P ∧ Q is true). Every proof has these elements, though it does not have to be written in a tabular format. And m ...

Mathematical proof

In mathematics, a proof is a deductive argument for a mathematical statement. In the argument, other previously established statements, such as theorems, can be used. In principle, a proof can be traced back to self-evident or assumed statements, known as axioms. Proofs are examples of deductive reasoning and are distinguished from inductive or empirical arguments; a proof must demonstrate that a statement is always true (occasionally by listing all possible cases and showing that it holds in each), rather than enumerate many confirmatory cases. An unproved proposition that is believed true is known as a conjecture.Proofs employ logic but usually include some amount of natural language which usually admits some ambiguity. In fact, the vast majority of proofs in written mathematics can be considered as applications of rigorous informal logic. Purely formal proofs, written in symbolic language instead of natural language, are considered in proof theory. The distinction between formal and informal proofs has led to much examination of current and historical mathematical practice, quasi-empiricism in mathematics, and so-called folk mathematics (in both senses of that term). The philosophy of mathematics is concerned with the role of language and logic in proofs, and mathematics as a language.

![[Ch 3, 4] Logic and Proofs (2) 1. Valid and Invalid Arguments (§2.3](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/014954007_1-d36c768aba23f0b4aa633cb9a2a27ee2-300x300.png)