Review Sheet

... Problem #1: Is it possible to rewrite the following IF function without using any ANDs or ORs? =IF(AND(A1>5,B1>10,C1,D1) If it is possible, then you have two IF statements that are logically equivalent. If it is possible, what test data do you need to run through both IF functions to make sure they ...

... Problem #1: Is it possible to rewrite the following IF function without using any ANDs or ORs? =IF(AND(A1>5,B1>10,C1,D1) If it is possible, then you have two IF statements that are logically equivalent. If it is possible, what test data do you need to run through both IF functions to make sure they ...

2.2B Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form

... Paper/pencil graphing with standard form: 1. Does the parabola opens up or down? 2. Does it have a maximum or minimum? 3. What is the equation of the axis of symmetry? Graph the line. 4. What is the vertex. Plot the point. 5. What is the domain and range? 6. What is the y-intercept. Plot it. 7. Use ...

... Paper/pencil graphing with standard form: 1. Does the parabola opens up or down? 2. Does it have a maximum or minimum? 3. What is the equation of the axis of symmetry? Graph the line. 4. What is the vertex. Plot the point. 5. What is the domain and range? 6. What is the y-intercept. Plot it. 7. Use ...

Chapter 3-1 Guided Notes Name___________________ Square

... Chapter 3-1 Guided Notes Name___________________ Square Roots Perfect Square- numbers such as 1, 4, 9, 16, and 25 are called perfect squares because they are squares of ________________ numbers. They have no decimals in the answer. Square Root- The opposite of ________________________ a number. One ...

... Chapter 3-1 Guided Notes Name___________________ Square Roots Perfect Square- numbers such as 1, 4, 9, 16, and 25 are called perfect squares because they are squares of ________________ numbers. They have no decimals in the answer. Square Root- The opposite of ________________________ a number. One ...

To evaluate integer questions that involve multiple signs:

... The addition of integers can be shown by moves on a number line. - Start at the first integer - Move to the right for positive integers - Move to the left for negative integers To subtract an integer, add its opposite. Example 1: Evaluate. a) (+3) + (+4) b) (-3) + (-4) c) (+3) + (-4) d) (-3) + (+4) ...

... The addition of integers can be shown by moves on a number line. - Start at the first integer - Move to the right for positive integers - Move to the left for negative integers To subtract an integer, add its opposite. Example 1: Evaluate. a) (+3) + (+4) b) (-3) + (-4) c) (+3) + (-4) d) (-3) + (+4) ...

Rules for Computation of Integers

... Look at the type of numbers you are to add (positive or negative) If the signs are the same (both positive or both negative) add the absolute value of the numbers If the signs are different subtract the absolute values of the numbers The answer's sign (+ or -) is determined by the number with the la ...

... Look at the type of numbers you are to add (positive or negative) If the signs are the same (both positive or both negative) add the absolute value of the numbers If the signs are different subtract the absolute values of the numbers The answer's sign (+ or -) is determined by the number with the la ...

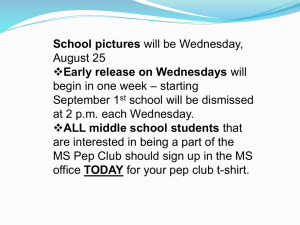

Tuesday, August 24

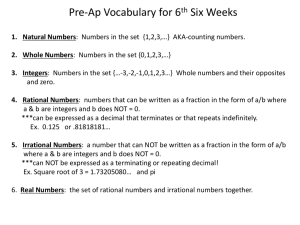

... as a/b, where a and b are both integers, and b is not equal to 0 Irrational Numbers Cannot be expressed in the form a/b where a and b are integers. Note: All integers are rational numbers because you can write any integer as n/1 ...

... as a/b, where a and b are both integers, and b is not equal to 0 Irrational Numbers Cannot be expressed in the form a/b where a and b are integers. Note: All integers are rational numbers because you can write any integer as n/1 ...

Basic Algebra Review

... b2 c bc b c b c b c b c b c b c combines different indices (e.g., a cube root times a fourth root), convert radicals to fractional exponents and use exponent rules to simplify (see IV above); result may be converted back to radicals afterwards. VII. Factoring polynomials: Simplify like terms ...

... b2 c bc b c b c b c b c b c b c combines different indices (e.g., a cube root times a fourth root), convert radicals to fractional exponents and use exponent rules to simplify (see IV above); result may be converted back to radicals afterwards. VII. Factoring polynomials: Simplify like terms ...

![[Part 1]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/008795996_1-7bdba077dfd2123ff356afe25da5d3ed-300x300.png)